Renewables

How is WA mining and resources tackling global warming?

WA’s mining and resources sector is working hard to reduce its carbon emissions, including transitioning from diesel generation to renewable power on site, introducing and developing electric vehicles and machinery, and investing in new clean energy sources. The state also produces many of the battery minerals that are needed for the world to achieve net zero.

What is net zero and why do we need to get there?

Net zero is the target of completely negating the amount of greenhouse gases produced by human activity, to be achieved by reducing emissions and implementing methods of absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

A carbon emission is carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere, often as the result of human activity such as burning of fossil fuels. Build-up of CO2 is a major factor in global warming.

Net zero is important because international scientific consensus is that achieving it by or before 2050 is needed to limit the impact of climate change.

Australia’s commitment

The Albanese Government’s Climate Change Bill 2022 enshrined into law an emissions reduction target of 43 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030, and achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

The renewables equation

Renewable energy, derived from sources that don’t run out, is a fundamental aspect of the pathway to the world reducing its carbon emissions and achieving net zero.

Research published by Net Zero Australia in August 2022 suggested Australia would need about 40 times the total generation capacity of today’s national electricity market in renewables, including an estimated 1900 GW of solar photovoltaic, to deliver on its net zero ambitions by 2050.

The road for mining and resources

The WA mining and resources sector is committed to the Paris Agreement and its goal of limiting global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, by reducing emissions to net zero as soon as possible and no later than 2050.

To achieve this the sector is investing in the new energies, technologies and fuels we need to deliver the emissions reductions required to meet Australia’s net zero targets.

Hydrogen – A future fuel

Catherine Simon is a Senior Process Engineer in Woodside’s New Energy Team, and CME’s 2023 Renewables Ambassador.

Catherine discusses how Woodside’s hydrogen projects help support a lower carbon future, and highlights the importance of Woodside’s partnerships with universities & start-ups to find and develop the necessary sustainable technologies to meet global demand.

Producing commodities to help the world

BHP Nickel West climate change specialist Samantha Langley discusses how her company is producing nickel sulphate for global electric vehicle battery markets at its state-of-the-art Kwinana refinery.

Different types of renewables

On-site renewables

New technology

New fuels

How WA is mining for a renewable future

Nickel

Lithium

Rare Earths

Bauxite

Silicon

Other minerals used in renewables that are mined in WA

Iron Ore

Iron Ore

Nearly all iron ore is turned into steel, a key component of wind turbines.

Cobalt

Cobalt

Without it batteries would be prone to overheating and have shorter lifespans.

Graphite

Graphite

The primary material used in anodes for lithium-ion batteries.

Vanadium

Vanadium

Projected to be a starting point for industrial batteries of the future.

Copper

Copper

Up to four times more copper is needed for EVs compared to internal combustion engines.

Take the renewables quiz

Answer these 10 questions to find out how much you know about the changing face of global energy technologies.

Read more about renewables

Interesting renewable projects from around the world

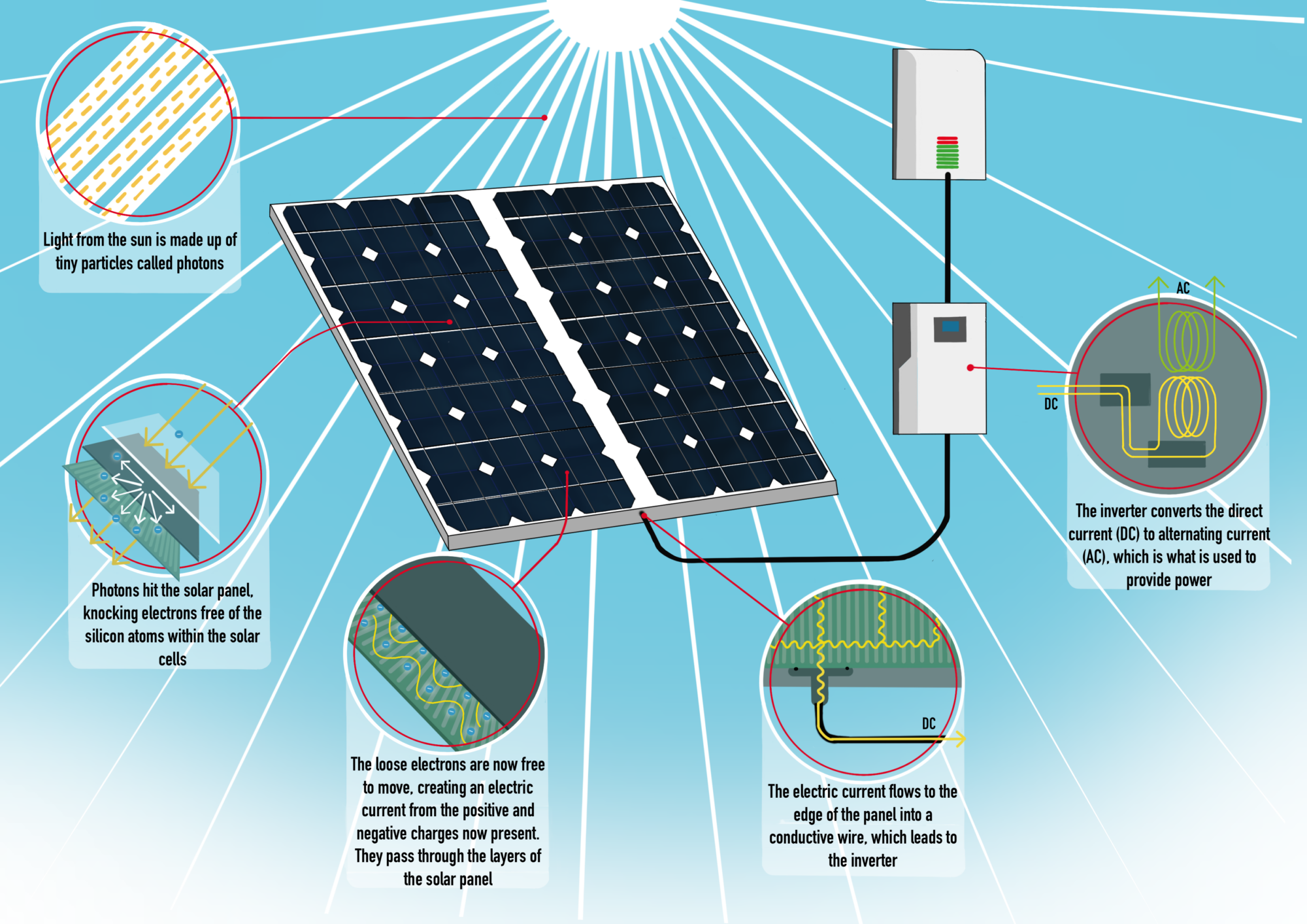

How solar panels work

From a scientific perspective, solar power relies on photons, or particles of light, knocking electrons free from atoms to generate a flow of electricity. This occurs when the sun shines onto a solar panel and energy is absorbed into the panel’s photovoltaic cells. A key ingredient in these cells is silicon, a commodity produced in WA’s South West.

The electricity generated is managed through inverters, which convert it to usable power – which can either be stored in a battery for later use or used straight away.

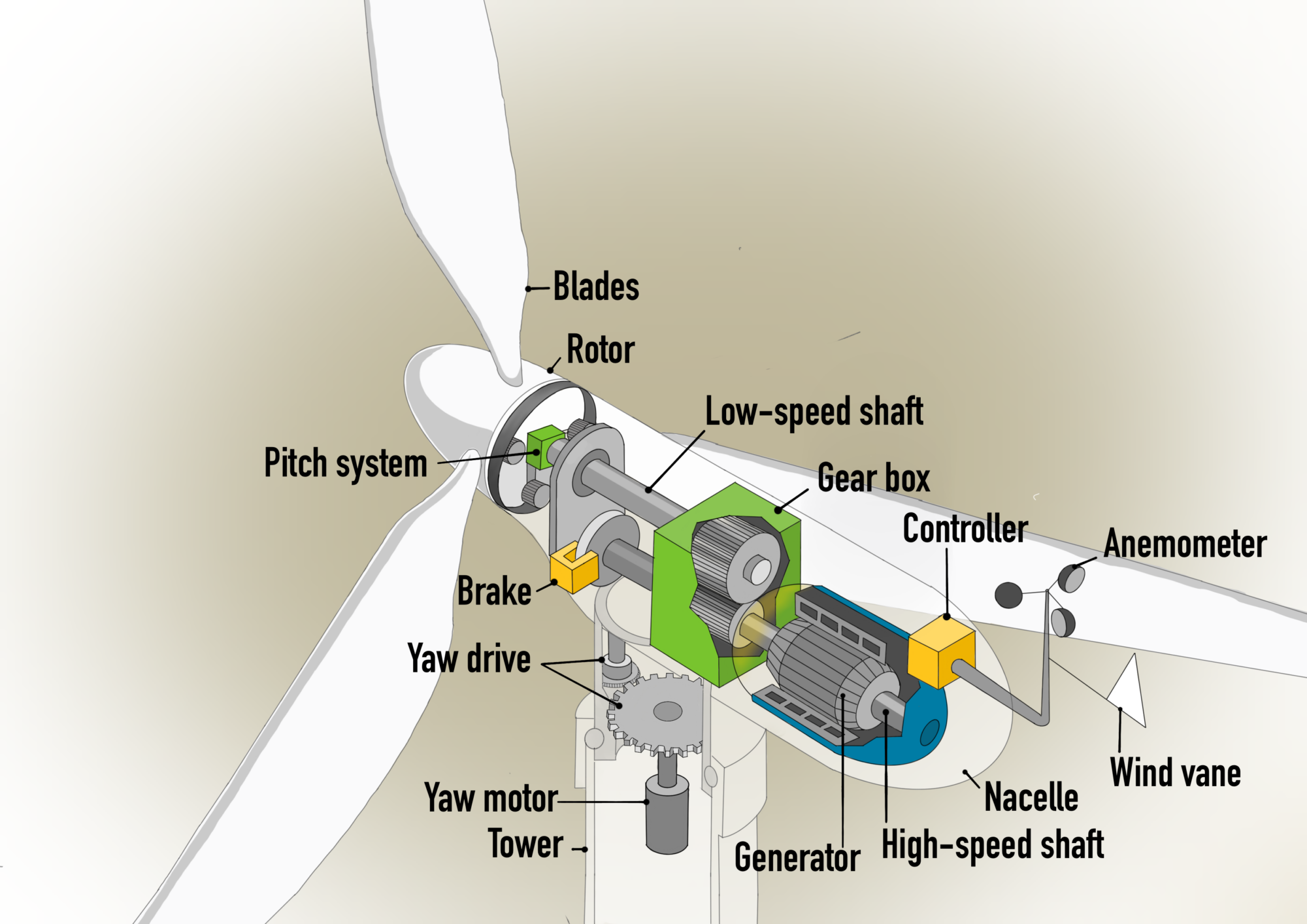

How wind turbines work

As their name might suggest, wind turbine blades rely on the movement of air to rotate. It doesn’t have to be particularly strong winds, with 12-14km/h enough to get the blades moving and start to generate electricity. However, speeds of around 50-60km/h will enable systems to generate a full capacity.

The mechanical apparatus of wind turbines are housed in a large casing known as a nacelle, which can weigh hundreds of tons. Kinetic energy created when the blades rotate is transferred to a generator which generates electricity. Similar to solar power, electricity created by wind can either be used immediately or stored via a battery.

How green hydrogen is made

Green Hydrogen is made by using electrolysis. Electrolysis is the process of using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

To generate the electricity for green hydrogen only renewables can be used. Hydrogen can be stored much the same way we do now with natural gas.

Hydrogen can be added directly to existing gas infrastructure for electricity generation and household heating.

Hydrogen can also be converted to ammonia for export or liquefied for use in fuel cells in heavy-duty vehicles such as trucks and bulk carriers.

Yara Pilbara is building a green hydrogen plant at its globally-significant operation on the Burrup Peninsula, while ATCO is developing a hydrogen production facility at the Warradarge Wind Farm in the Mid West.

SAFER

SAFER

Find out how WA’s mining & resources sector is prioritising safety in its operations.

SMARTER

SMARTER

Find out how the WA’s mining & resources sector is using technology to become smarter.

CLEANER

CLEANER

Find out how the WA’s mining & resources sector is using renewables to become cleaner.

SITE REHAB

SITE REHAB

Find out how the WA’s mining & resources sector is refining techniques to rehabilitate old sites.